I think that one of the things that can make or break a novel is the setting.

You might be saying, well, no duh -- or you might be wondering what on Earth I mean: After all, an exciting/interesting set of characters, emotion-evoking writing, and/or a great plot should serve if the setting fails, shouldn't it? Many of Shakespeare's plays, it could be argued, have a mutable setting, and I certainly wouldn't disagree with you on that point (my favorite version of Richard III is set as a World War I allegory, eschewing everything but Shakespeare's own mentions of the War of the Roses!). But I'm beginning to note that 'setting' doesn't just apply to things as superficial as historical era or geographic location.

So, I shall pose a question: Could you set Wuthering Heights away from the moors, and still retain the innate feel of the setting it had before?

|

| Oswaldtwistle Moor (Orphan Wiki, Wikipedia Commons) |

Setting is inevitably tied to theme; you can look at countless other works and see that. Though works of genre fiction, C.J. Sansom's Matthew Shardlake mystery books are rooted firmly in Tudor England, a setting in which the main character is treated with flippancy, derision, and even sometimes disgust because of his disability and his status as a lawyer -- and further, being a contemporary author, C.J. Sansom uses the status of women in that era quite often to make statements on sexism and illustrate certain qualities in his characters. If you set Revelation in the 2000s, Shardlake's views on equality and his kindness toward women would be a pleasant surprise, but not shocking or immediately endearing; in fact, given his beliefs in the original Tudor-set novels, he might seem a little stiff or old-fashioned. And while lawyers are still scoffed at and people with disability still suffer prejudice, he would have a lot easier of a time than he did in the early 1500s.

The setting of that book gives the reader an immediate connection with one of the characters, as both an outcast and a man with borderline revolutionary ideas on gender roles; even his inner religious conflict is flavored by the Reformist/Papist tensions at the time. Everything about Sansom's mysteries is painted by the fact that his characters are living in London under King Henry VIII. It would be unthinkable to tear them away from that setting.

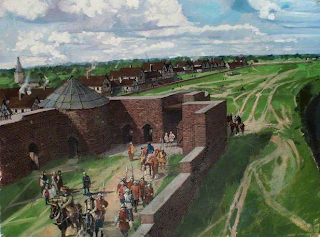

|

| Illustration by Ivan Lapper |

Without including too many spoilers (since I have no way of knowing how many of you have read it before), setting also figures greatly into Frankenstein. Being a piece of period literature, the reader has to doubly consider the setting -- both when it is set and when it was written. Thankfully, the two aren't terribly far displaced, but it's still quite different than reading a contemporary work written in the late 1700s; the narrative is rife with Enlightenment and Early Modern ideals. This is a story that is almost entirely a product of its time, from the sneaky references to the Natural State and social justice to the outright classical/theological allusions and natural philosophy name-dropping. If you've never read it before, you might even laugh aloud in places at the weirdly-placed digressions into tourist-y description. (Maybe even if you've read it before. Catches me off guard every time I read it.)

And yet, it is absolutely possible to translate it into the modern era, because in the end it's not about the obvious setting, just like Emily Bronte's work isn't about the setting.

So my answer to the original question would be that you can indeed set Wuthering Heights elsewhere, and almost anywhere -- the story itself, with its isolation and wildness and desperation, has Northern England's vast rocky moors engraved into its soul. To translate it and retain the real meat of the setting would be effortless because the story itself is the setting, just as in Frankenstein -- the narrative itself is a product of its setting, from its morals to its characters. The characters are embodiments of their time's (and author's!) moral disputes and musings.

You see this a lot more with literary fiction, I think, because setting in genre fiction tends to be an excuse for escapism and cool period description. Sansom isn't the only author that does this, but there are a lot of contemporary historical fiction writers that don't, and mostly they're those that are esteemed as literary; Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall is lush with the moral conflict of the time period, such that the word "doublet" or a mention of rushes on the floor can jar you out of the conflict if you aren't familiar enough with the time period to know it's not just coming out of nowhere. She doesn't need to mention the setting very much because the thoughts and struggles of the characters are so thick with it. And while Umberto Eco offers a rich setting to get lost in in almost all of his books -- he's technical about the setting to the point of massive descriptions of monastery life or medieval religious conflict that can last pages or even chapters -- that's not the point, in the end. If you examine his work as a literary critic and not just a lover of history, you can get just as much if not more out of it. The theme itself stands out starkly, and is timeless.

This post is probably a lot more rambly than a lot of mine since I've been out a lot of days and haven't attended several classes that were probably enlightening -- and I realize it's not really about anything specific from English class, other than Wuthering Heights. But the presence of setting has been weighing on my mind as both a writer (National Novel Writing Month, you say? What? [weak, horrible laughter]) and a reader, and I think it's an important thing to consider the entanglement of the setting with the ideals and themes of the plot; if I'm reading a book with a setting that isn't reflective of its plot, and a plot that isn't reflective of its setting, something that I can't put my finger on feels off.

The time and ideology should breathe through its characters. It should feel alive, no matter whether it's a Shakespeare play set during WWI or some outlandish adaptation of Wuthering Heights set in the bustle (but stark, strange isolation) of New York City.